from an on-line conversation I had with an advocate of contact stage slaps. This was my response …

( FYI: since this was originally posted, more information has come out in medical journals indicating that during a slap, the brain moves violently against the skull, and can cause “coup” injuries. This is a sub-concussive blow. Every sub-concussive blow causes brain injury. Let me repeat: Every sub-concussive blow causes brain injury. You don’t have to see stars or get dizzy for a hit to damage your brain. )

message to morgan46@ehow:

Thank you for your e-mail. I still want you to consider revising the way you teach the stage slap.

I agree that most of the time the contact slap works. But it is the one percent of the time when it doesn’t that worries me, because when it goes wrong it goes horribly wrong.

Here is a more full explanation of why I am so against it, followed by a detailed instruction of how to do a non-contact slap:

There are some stage combat experts who insist that an actual contact slap to the face is perfectly safe as long as it is modified slightly. I have seen videos sold by these same professionals showing actor/students facing each other and trading slaps back and forth to prove the safety. Those experts are wrong. The contact slap is inherently unsafe. The slap to the face sends more actors to hospital emergency rooms every year than all of the other techniques of stage combat combined. This includes knife fights, broadsword fights, swinging from ropes, gunshots … all of the other techniques of stage combat combined.

Actors are often taught that all one needs to do to safely slap someone in the face is to cup the hand slightly, keep the fingers and wrist very relaxed, and go for the fleshy part of the cheek. It is true that most of the time it causes no injury, which is why many assume that it is safe. But when this contact technique goes wrong, the results are devastating.

In a perfect world, the slapping hand will strike at exactly the same spot every single time, but that is simply unrealistic. If the hand is perfectly flat, the hand is also tense, therefore has become rigid. When a hand is relaxed, the palm forms a slightly shallow cup shape. When that cup strikes the cheek, the air inside becomes pressurized and searches for release in the line of least resistance, which makes that satisfying popping sound as it slips by the fleshy skin of the cheek. However, if the hand drifts a mere inch closer to the victim, the ear is now inside the coverage of the hand. The pressurized air is still looking for a means of escape, and it’s found it – right down the ear canal. At the bottom of the canal is the tympanic membrane – the ear drum – which easily bursts. If the membrane doesn’t heal properly [all too common even with immediate medical attention] or if an infection develops [which is highly probable] the actor can expect temporary or permanent, partial or complete, hearing loss in the affected ear. Even one finger tip tapping the ear canal can pop an eardrum.

If this were the only bad thing that can happen to the actor, it would be reason enough to ban this practice, but there are other injuries which also occur – every year. If the hand is flexed a little, the face is hit with not a cushion of air but with the outer edge of the hand, or the hard ridge where the fingers meet the palm, or worse, the heel of the palm. In other words, bone strikes face. This can and does lead to dislocated jaws, broken cheek bones, broken hands, broken cartilage of the external ear, broken teeth, split lips – nasty stuff.

The damage need not occur only on the first contact of the slap itself. Many have escaped injury on the initial slap only to have the trailing fingers scrape across the near eye or break the nose. Some have been taught that, in order to avoid all of these potential dangers, the slap can be delivered lower, to the side of the neck. Very poor advice, as this can lead to a bruised trachea, and in one instance a slap collapsed the carotid artery and the victim died from lack of oxygen to the brain. Died.

No one should have to risk deafness, blindness, broken bones or death because of a play. But even if we could make the contact slap completely risk free, there is still another reason not to do it. It leads to bad acting for both the aggressor and the victim. The aggressor has to stop acting for a moment while she worries if the slap has really done any damage, which is the opposite of the feeling she is trying to convey to the audience. As for the victim, he usually ends up with a look of stoic resistance just before the slap – not exactly helpful in trying to sell the idea that the slap has come as a surprise. The timing can suffer, because most actors tend to get a bit “slap-shy” after being struck in the face a few times in rehearsal, and then start to react to the slap before the hand has started moving. Also, the pain received is real pain, therefore the reaction is the actor’s, not the character’s. It might be similar to the character’s, but at that moment the actor has removed himself from the world of the play and lives completely within himself as his body deals with the pain. All of the work of trying to create a world specific to the playwright’s intention is thrown out the window, and the audience has to wait for the actors to regroup and find the characters again. This isn’t acting; it’s the opposite of acting. It’s the equivalent of rubbing onion juice on your cheek in order to bring up tears.

On occasion, directors will tell me that they would rather that the actors hit each other because it is very difficult to make the simulation look real. Yes, that’s true. It is hard work, harder than any other simulation you will ever ask your actors to do. But since it can save them from permanent injury, just suck it up and add the extra rehearsal time and work it ad nauseam until you can fake out five observers looking at the slap from five different vantage points.

I have more than once heard an actor tell his partner to “just go ahead and slap me – it’ll keep me in the moment and it will look better”. I’ve noticed that the offer is never made if he is supposed to be struck on the head with a baseball bat. Well, if they can make a simulation of being clubbed work to the audience’s satisfaction, they can do the same with a simulation of a slap. I obviously feel strongly about this, so strongly that I will not work for a director who insists on having the actors perform an actual contact face slap. You shouldn’t either.

* * * *

Now, let’s get to the simulation. A real slap to the face, especially as written in most Western plays, comes as much of a surprise to the aggressor as it does to the victim, so in the simulation we need to remove any hint of premeditation. So there isn’t going to be much of a wind-up nor follow through. If anything, the body and even the rest of the arm will stay neutral and the slapping hand will look as though it had a life of its own from the wrist outward. Let’s try a difficult slap first, and that’s with the aggressor’s back to the audience.

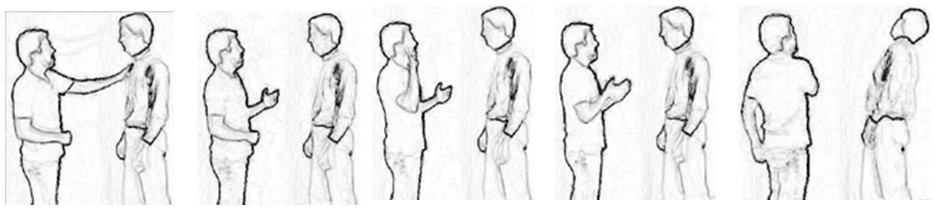

Set-up: As the victim crosses slightly upstage, the aggressor uses the fingers of the left hand to touch the shoulder, stopping the victim from continuing, by happenstance stopping directly upstage of the aggressor. This is a small movement that can happen several lines before the slap, for it merely establishes distance. We can call this the “pre” set-up. Once the left hand is no longer seen by the audience, it can move to its target position – right in front of and against the solar plexus, palm turned up at about 45 degrees.

Picture: On the cue for the slap, the right elbow stays tucked against the body as the right hand flies up almost to ear height. Don’t short change this step, because there is no body English that goes along with this simulation. You must give the audience a brief look at the back of the hand or they won’t register the slap that is to come. But the elbow must not move.

Action: The hand, and only the hand, moves quickly here from right ear to left ear. Along the way, as it disappears from view, it scoops down to the target hand, makes contact with a light slapping sound, and then continues to its final position. Think of slapping water out of a bowl being held by the left hand, and throwing the water over your left shoulder. Do not move either elbow, don’t move your body, and you don’t need to move the target hand either. This is a tiny little movement; not an action that has the force to drive someone through a wall, but just enough to turn the face slightly.

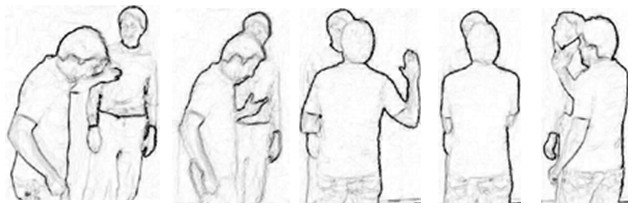

ASM’s view, self slip-hand knap. Notice how far the victim is from the action.

ASM’s view, self slip-hand knap. Notice how far the victim is from the action.

Reaction: The aggressor must show the audience the fingertips of the right hand over the left shoulder for just a brief second, and the left hand must simply appear down by the left side. We want the audience to think that it was there the whole time, that way they won’t think that it was part of the action. Again, eliminate all movement except for that of the slapping hand. The victim must wait until he hears the slap sound before moving the face.

No matter what the relationship was between the two characters, once a slap has occurred it means that the world of these people has changed forever. One person has decided that words alone cannot express emotion, and that violence – the specific intent to cause physical pain – was the only remedy. There is no ignoring the transgression. The characters may make up afterwards, but the damage to the relationship will be there forever. Both characters know it, the audience knows it, and that is why the damage is far greater than the act. The audience now needs to know what will happen next – where will the relationship go? – and so they will look at the victim’s eyes for help. That is where your focus should be as well. The slap is over in a second; the emotional scar may last a lifetime.

I said that this simulation is the most difficult, so if you master it, everything else is a piece of cake. An easier version is to reverse positions, having the victim step slightly downstage and then turn his back to the audience. Now he can clap his own hands together, or even just use one hand to slap his chest, although the chest slap is a deader sound, so I prefer that the victim simply clap his hands. This one must be a slip-hand knap, with one hand held stationary as a target and the other traveling in a straight line from down by the hip to the target hand to the “struck” cheek as part of the reaction. The aggressor can stand a little further back and his hand need not dip so low, although I still like the fingertips to scoop underneath chin level so that the victim knows he has nothing to fear. In any case, the slapping hand need never get any closer to the victim than halfway between the two actors.

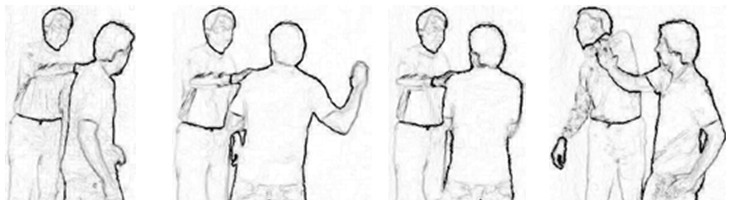

A more aggressive slap, audience view, shared slip-hand knap. Notice how the elbow starts away from the body, suggesting more premeditation.

A more aggressive slap, audience view, shared slip-hand knap. Notice how the elbow starts away from the body, suggesting more premeditation.

As both actors feel more secure in the knowledge that they can’t hurt each other, the director can keep making adjustments to make sure that the audience is fooled by this illusion. As everyone masters these techniques, slowly turn out the relative placement of the actors. Instead of one being full back to the audience, try moving them so one is three quarters front and the other is one quarter front. The body placement will have to change slightly, and the path which the arm takes may need to change as well, but it is possible to open this simulation up quite a bit, especially if the actors are in motion slightly just before the set-up.

This kind of simulation can be a pain to work through, but it is definitely worth the effort. I have yet to find a circumstance in which there was no alternative to actual contact. To give you an idea, I once choreographed the fight scenes for a theatre-in-the-round production of Macbeth, and in this production for some reason a general slapped a soldier in the face. The actors were surrounded by the audience so there was no hand that could disappear from view, and we couldn’t provide the usual cheat of doing an off-stage noise. We finally worked it so that when the soldier finished his line the general stood for a moment in livid silence and then turned slightly away, as if the soldier was off the hook. Just as the soldier relaxed with a sigh of relief, the general suddenly turned back and savagely struck him. The soldier instantly raised his hand to the side of the face, and the general let his own hand hang in the air at face level. The audience heard the slap, and they were sure that they had seen the soldier’s face brutally struck. But the actor had merely been slapped on the shoulder. So long as the actors believed the illusion, the audience did as well, because they were given the right picture before and after the sound.

* * * *

When I started out in this business many decades ago I had to give and receive the slap to the face just as you, morgan46@ehow, are now teaching it. Luckily a new generation of actors and fight choreographers have moved up through the ranks, skilled in the techniques of non-contact stage combat. I would turn your phrase around and say that if you cannot find an alternative to actually hitting another actor, “you have no business taking on a stage fight”.

Richard Pallaziol

Weapons of Choice