A Little Night Music

As Russian roulette is not possible to perform with a muzzle-loaded gun, you can’t use a single shot pistol or even a percussion revolver for this show. You just can’t. It has to be a cartridge revolver (breach-loaded), so the gun would have had to been designed and built after 1875.

Aida – Elton John/Tim Rice Musical

You might want to go back to the first section and re-read the section on Egyptian fighting. Then you are going to have to toss all of that info aside and just use whatever will make the director happy. Even if you do happen to find a good compromise sword/dagger that looks vaguely Egyptian, you are still stuck with the fact that even the soldiers never wore their weapons, so more compromises need to be made. Since there is no point in trying for historical accuracy in this musical, don’t worry about it. Whatever you pick (Bronze Age, medieval, fantasy) will work fine for this show.

Aida – Verdi Opera

If this is staged with greater respect for Egyptian culture, this gets much harder to prop, for the same reasons mentioned above. Usually it’s simply easier to go with Greek/Roman weapons and call it a day.

Annie Get Your Gun

An expensive prop show if done faithfully to the Broadway script, but even if shortcuts are made, start saving your pennies well in advance of mounting this show.

The historic Annie Oakley used several types of rifles and pistols for her sharpshooting. Her favorite was not a lever-action rifle at all, but a Marlin repeating rifle, .22 caliber. It was the Broadway musical which had her and Frank use lever-actions, so that is what we are used to seeing. [In her song, You Can’t Get a Man With a Gun, there is a reference to her “Remington”, but this is mere songwriter’s license and doesn’t mean that you have to find a Remington rifle for the show. Anyway, there is no specific look to a “Remington” any more than there is to a “Chevrolet”.] There is no doubt that she was a tremendous marksman, perhaps the finest that ever lived. But it should also be noted that for some of the trick shots, especially firing at balloons, some of her rifles were loaded with special cartridges filled with sand instead of a lead bullet. The sand expands in flight and covers a wide area which can easily pop a balloon or even shatter a shot glass, a trick still used in movie westerns. It was also done for some of the specialty numbers of the original Broadway version, but is so dangerous that no theatre would be allowed to do that today. Remember that until recently most guns shot onstage were real weapons loaded with blanks.

Again, the Broadway tradition has Frank and Annie using lever-action rifles, but simple semi-auto repeaters are also correct. The cost comes not just with the rental cost of each rifle, but the number of firing rifles required for the last scene, where Annie keeps “missing” with each rifle she picks up. So how can you reduce costs for this show?

1] Have the gun cases open away from the audience’s view, so they never get a chance to see what is inside. That way the same two or three guns can be exchanged yet it can seem as though there are half a dozen inside.

2] Use cheaper guns. One production went so far as to use revolvers instead of rifles for the shooting match and was able to cut the overall weapons costs to one quarter of what it might have been.

3] Take a page from the latest Broadway remounting of the show (the “Bernadette Peters version”) and have the drummer do rim-shots instead of having the guns fire at all. I love this alternative, for it eliminates the inevitable headaches from misfiring and jamming guns, eliminates the danger to all the actors on stage, and drops the cost to a tenth or less of what it might ordinarily have been.

In the earlier scenes, Annie is introduced using her old hunting rifle. As the historic Annie was born in 1860 and started shooting at age 9 (1869), this old gun should be a percussion lock or perhaps even a flintlock rifle. The family couldn’t have afforded a cartridge rifle, and the lever-action hadn’t been invented yet.

The competition against Frank Butler took place in 1876, when she was sixteen years old. He might have had one of the newfangled lever-action rifles, but they were certainly state of the art machines, and prohibitively expensive for her to have even seen, let alone handled, one. Annie and Frank joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show much later, in 1885, by which time she was a widely recognized expert in shooting any type of firearm.

Random art note: This show, with one number insulting to Native Americans and the entire script generally demeaning to women, is still popular enough with no sign of it dying away. Modern versions of the show usually try to add a tongue in cheek eye-rolling slant on the final scene so that it is a little less degrading, but as in Taming of A Shrew, you can’t get around the words that are there. But why was the show even written this way? Especially since the historic Annie was a strong, independent woman, and the Wild West Show always treated her as a star of higher rank and respect than any of the other performers.

Annie Get Your Gun first opened in 1946, just after WWII, at a time when thousands of newly discharged soldiers were returning home to find that most of their pre-wartime jobs had been filled, and competently performed, by women. The War Department applied tremendous pressure to make sure that women relinquished those jobs (or were fired from them) so that the returning veterans would more easily slip back into their civilian roles. To have a show such as this that depicts a woman of accomplishment willingly slide back into subservience was comforting and appealing at the time.

Anything Goes

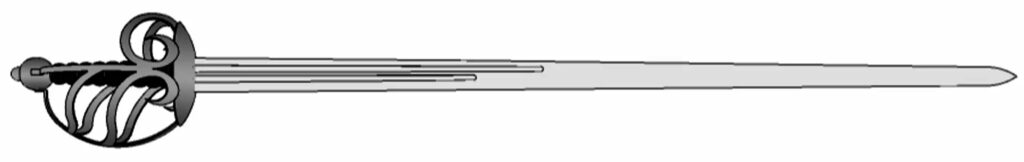

There is a great moment when Lord Evelyn Oakleigh rushes on in his nightshirt waiving a “broadsword”. But we’re not talking about a knight-in-armour Excalibur thing. The playwrights were British, and what is required here is from the British definition of broadsword, which is a heavy infantry straight sabre of the 18th and 19th centuries (think American Civil War), not the medieval broadsword.

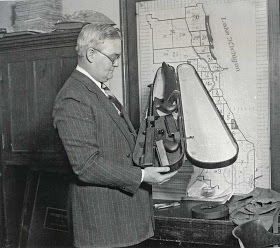

The Tommy Gun in a Violin Case. I’m sorry to tell you that a complete Tommy Gun doesn’t fit inside any instrument case, let alone that of a violin. Only the dismantled parts of the weapon were ever transported this way, and even then it had to be the stripped down version with no buttstock and certainly not the distinctive round drum that holds the bullets. The gun would be reassembled once the gangster was in a safe or hidden location, but it was impossible to simply open the case and start using the gun. No, this moment in the show is pure fantasy, so a modified truncated Tommy Gun and a special case will have to be found or built.

Arcadia

A “rabbit pistol” is called for, but as far as I’ve been able to find out, there is no reference to such an item outside of the world of this play. We can safely assume that it is a small caliber flintlock or percussion lock pistol, but not a fancy heirloom piece. The term is probably similar to the modern “squirrel gun” or “deer rifle”, just an offhand way that the owner of the firearm describes the primary purpose of having the weapon. Someone shooting at rabbits with a pistol is not trying to hunt down dinner, but is just “joy shooting” – the equivalent of playing a video game.

Also in this play is a reference to a Barlow knife, which is merely a brand name for a popular small folding pocket knife of the period.

Arthur

see “Camelot”

Assassins

I am using the caliber descriptions on the guns only for identification purposes, but the fact that we happen to know what the caliber was for a specific weapon shouldn’t dissuade you from using a similar looking gun with a different number. Remember that caliber refers to the internal barrel diameter, so if you find something that looks OK which is 6/100’s of an inch larger than the historical gun no one will ever see the difference.

John Wilkes Booth 1865 A Philadelphia single-shot Derringer was used to shoot Lincoln, so in the final tableau, and in the opening scene, this should be the gun he holds. He also had with him a good sized Bowie knife that he brandished before jumping. The Two-shot hadn’t been invented at the time of the assassination. It was still twenty years and a completely different firing system away. Booth fired the only shot he had from his blackpowder Philadelphia, then had to fight Major Rathbone (who was sitting in the balcony with Lincoln) using a large knife. During the scuffle, the useless pistol was dropped to the ground, which is why we know what he used. It was recovered and is now in the possession of the National Park Service.

Colt 1851 percussion six-shooter, for the shoot-out and suicide in the barn. Booth actually had two revolvers and a carbine rifle with him at the time of his death, but only fired his Colt revolver. Whether he shot himself or was shot by one of the posse was never satisfactorily established.

Guiteau 1881 British Bulldog .44 cal, silver handled.

There really is no such thing as a silver handle for a gun, and the script describes it as “silver mounted”, an interesting phrase that defies easy explanation, for the term is used for sword hilts but not gun grips. Many assume that the reference is perhaps to a silver or nickel plated gun, but that’s not really the same thing. Be that as it may, the script has it wrong on several counts. After his arrest, Guiteau told reporters that he felt it a shame that he wasn’t able to get a gun with an ivory grip, feeling that the gun would look better when it would be seen by millions in a museum someday. He actually ended up purchasing a plain black version of the gun with a rough wooden grip. [The gun itself no longer exists, but a clear photograph of it is in the Smithsonian archives.]

Czolgosz 1901 Iver-Johnson .32 cal, owls on the side, black grip.

The owl was the logo of Iver-Johnson Firearms Company, and is set into the pattern of the grip mold. Even when holding the gun in your hand, it is awfully difficult to see the logo. Certainly the audience can never see it. Don’t sweat over this minutia which is completely insignificant. [I hate details like this that are thrown into scripts but provide no benefit to the production.] The Iver-Johnson was a five shot top-breaking revolver, meaning the frame was hinged at the bottom of the frame. This allowed the barrel and chamber to swing down to expose it for loading, just like a break open shotgun.

IMPORTANT! It can be dangerous to use any firing pistol, stage-safe or real, for Czolgosz if you follow the stage directions and history. Stage guns usually have blocked barrels, which prevent any discharge from flying out of the barrel, and this is the only kind of firing gun that should ever be used onstage. Since Czolgosz is usually standing down center to shoot the invisible McKinley, pointing straight out at the audience, then of course there is no option but to use a gun with a blocked barrel anyway. But he is also supposed to wrap his gun in a handkerchief – it’s how he got it past the receiving line, and it’s mentioned in the lyrics. Guns that fire must vent in some direction, and the guns with plugged barrels generally vent through the side or the top of the gun. If that vent is blocked with a handkerchief, it can easily burn the fabric, starting a fire and/or injuring the actor’s hand. Both events have happened many times in the history of this show. To prevent this, you have three options:

1] go to black-out and have an off-stage gun provide the shot.

2] go to blackout and make sure that Czolgosz completely removes the handkerchief before firing. He doesn’t have much time, and the audience can still see the white fabric during the fade out.

3] use a very well fireproofed handkerchief. Even then only loosely wrap the fabric around the gun. A tight wrap could cause a secondary pressure explosion directed back to the actor’s hand, in a worst-case scenario sending the blast through the actor’s fingers.

Zangara 1933 cheap 5-shot .32 cal revolver, does not fire until final scene.

The gun is very similar to the Iver-Johnson above, nickel-plated with black rubber grips, but this gun has an exposed hammer and a different logo on the grip. There is a reason why the gun looks so much like Czolgosz’s. Iver Johnson also made a line of very cheap handguns, made to the same dimensions but of inferior material and looser tolerances. These were marketed under the name “U.S. Revolver Co.”, so as not to hurt the Iver Johnson brand name.

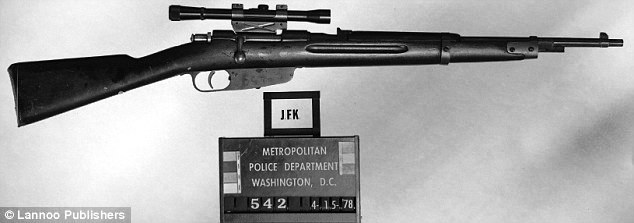

Ozwald 1963 Mannlicher-Carcano bolt-action rifle with scope and .38 cal revolver.

Just as with Booth, one gun, the rifle, was used for the assassination and another, the revolver, was with him when he was arrested/cornered.

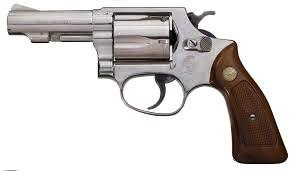

Sarah Jane Moore 1975 nickel-plated .38 cal Smith & Wesson revolver; 4” barrel length.

Moore’s gun most likely had the thin grip as shown, but could instead have had a more standard military grip, although it would have made handling and concealing the gun more difficult.

The same gun is supposed to be able to fire several times (see Fromme below for another option) and also be loadable onstage. That presents some difficulties, since most theatres need to keep the sound down to a manageable level, which means .22 caliber. Those blanks are less than a quarter inch wide, so can easily fumble through the actor’s fingers. You can get blank fire guns that are of larger caliber, but you’ll need to get specially loaded blanks that are quiet enough for actors to use without earplugs. The script asks for something even more difficult, namely that Sarah be able to open the loaded gun and accidentally let the bullets fall out of the chamber and onto the floor. What follows is a very funny bit, but blanks that are of the correct caliber usually stick to the chambers of stage guns pretty well and don’t fall out that easily. Real bullets for real revolvers do, but of course you’re not going to do that. The best way to go with this is to have her palm a handful of dummy bullets and let them drop instead. This is better than dropping the blanks anyway, for the dummy rounds can be much larger and easier for the audience to see what President Ford is doing after he comes into the scene.

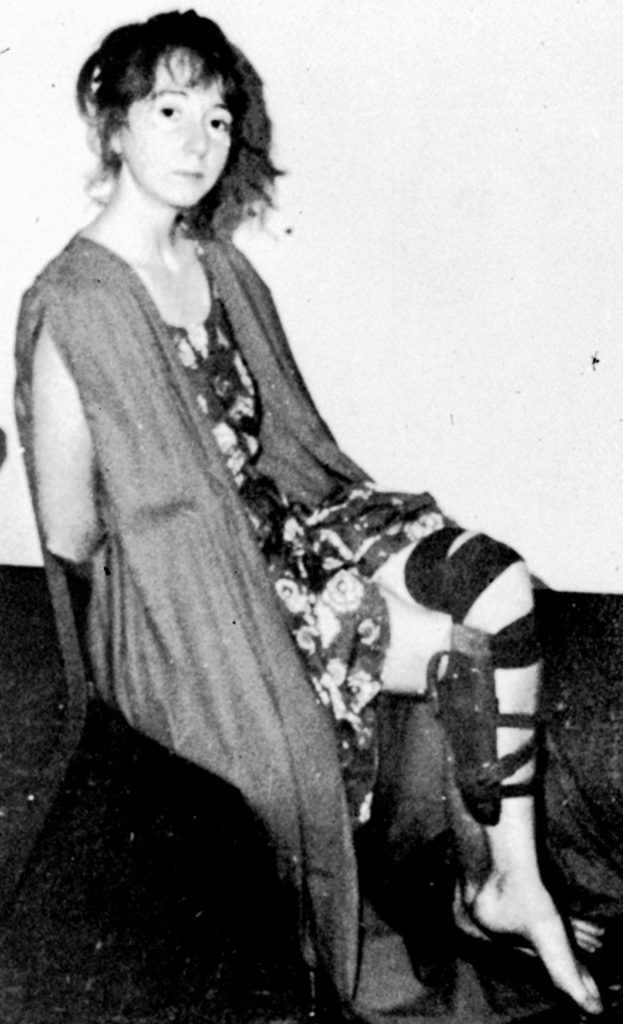

Lynette Squeaky Fromme 1975 Colt semiautomatic .45 cal pistol, model 1911, leg holster.

Apparently, her gun was a full-sized semiauto, so she is going to have quite a hefty bulk on her leg. She did not use an ankle holster. She wore this on the inside of her left leg at the calf, as FBI photos at her arrest clearly show. It was a regular full-sized holster, and she used several yards of leather tortuously wound around her thigh and lower leg to keep the thing secured.

[By the way, it was noted that when the police recovered the gun, it had four rounds in the clip but the chamber was empty. Fromme was waiting to fire the gun, but had not worked the action to bring the first round into the chamber. Although she later said that she had purposely kept the chamber empty, it seems that she was unaware of how a semi-automatic pistol works. Had she had a chance to fire the gun, she would have pulled the trigger to no effect.]

The loudest scene in this musical is the “chicken bucket scene”, where Fromme and Moore nearly empty their guns firing at a cardboard bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken. This poses a problem with not just the noise but also the expense of firing that many times and the larger problem of finding a safely firing semi-auto for Fromme. Curtain Call Theatre in Massachusetts came up a brilliant idea that took care of everything. They had Moore and Fromme literally yell out “bang” for each shot, the characters playfully pretending to shoot, Just when the audience is comfortable with the bit, Moore accidentally fires a real shot from her revolver. Both women are shocked, as is the audience. The moment is funny and compelling, and the single shot is much more effective than the multiple rounds that the script calls for.

Byck .22 cal revolver. No specifics that I’ve been able to find. Newspaper accounts of the time only mention that he had stolen the gun from a friend, but we are not told what kind it was.

Hinckley 22 caliber short-barreled revolver, Rohm RG-14

In the final scene all of the assassins face the audience and fire simultaneously directly at it. In most theatres that is simply going to be too much sound, so you will need to reduce the number of guns that are actually loaded to just a few of the actors. Also, if any of your guns have open barrels and there is any chance that some of the discharge is going to travel towards your audience, don’t fire those guns. All you need is to have a tiny spark reach someone’s face and you have instant lawsuit.

In the “gun song”, many directors have the actors dry fire their guns throughout the number. That’s fine, but remember that dry-firing (“clicking”) will sooner rather than later cause the hammer to break off. If you have rented the gun, you’ve just doubled the props cost for the show if even one of the guns break. If you have purchased the gun, you are in for a hefty repair bill. Either way, dry-firing is going to cost you a lot of money.

Batboy; the Musical

A deer rifle is mentioned, but the character comes in having bagged a couple of geese. Well, he didn’t do it with a rifle unless he’s the next Annie Oakley, and if he did it with a deer rifle there wouldn’t be much goose left. But, what, you’re worried about plausibility in a show called Batboy?

The Bear

SMIRNOV. [Examining the pistols] You see, there are several sorts of pistols. . . . There are Mortimer pistols, specially made for duels; they fire a percussion-cap. These are Smith and Wesson revolvers, triple action, with extractors. . . . These are excellent pistols. They can’t cost less than ninety rubles the pair. . . .

These lines get some people a little confused. Smirnov has not brought out any Mortimer pistols. He’s not saying that there are Mortimer pistols in his hands, but that in the world there exist several types of guns. He starts off talking about pistols in general, and tosses out the term in a vain show of knowledge in order to impress the young lady. [A Mortimer pistol was a very distinctive single-shot percussion pistol that was in fact designed only for target shooting, never for duels.] What he has brought out are two identical revolvers.

The specific guns that we do see are described as being Smith and Wesson and having certain attributes – triple action, and having an integrated ejection rod (“extractors”). Triple action in this case refers to the mechanical-action capability of the hammer and its interplay with the trigger, and the audience is never going to see that. Neither can Smirnov, because it is not something that can be seen. He is either bluffing about his knowledge or he really is a minor expert in guns and their attributes. Be that as it may, the only part of the full description that is visible is the ejection/extractor rod. It’s the part of Western style guns that looks like a thin barrel riding underneath the regular gun barrel, but is actually a push rod that allows the user to push out the spent brass cartridges from the cylinder after the gun is fired. It is a small detail that very few in the audience will know about, so if your prop gun doesn’t have one, I wouldn’t lose too much sleep over it. As for them being Smith and Wesson, the company made over a dozen distinct revolvers during this period, and the description in the script gives no indication of what the profile of the gun looks like, so you have a good chance that whatever gun you find will look like one of the Smith and Wesson’s from the turn of the century.

[In another of his works, a short story that takes place in a gun shop, Chekhov uses the same two gun references. Apparently, he had picked up these two bits of information somehow, and used them in his writing when he had the chance. They seem to be the sum of his gun knowledge.]

Beaux Stratagem

At one point in the play, Lady Bountiful appears carrying a “pike”, so described in the script. That’s not what the playwright really meant. A pike is a long thin spear, eight to twenty feet in length. Instead, the item needed is a short halberd. (As is usual with the plays of Ken Ludwig, mistakes of history, detail, and nomenclature abound, especially when it comes to weapons.)

Big River

see Tom Sawyer

Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson

Whatever the merits of the show itself and/or the political critique it offers concerning American history, one thing should be kept in mind when trying to make sure that the costumes and weapons are correct for the period: don’t bother. Jackson lived in the late 18th and early 19th century, and died in 1837. That is long before cowboys as we recognize them, and before revolvers and breech-loaded rifles were even invented. This is a purposefully silly musical that has no relation to historical accuracy.

Bonnie & Clyde

Both the cops and robbers had remarkably similar items, mainly because the Barrow gang got most of their firearms from thefts from national armories. Both they and the police used automatic rifles, shotguns, and handguns

For the automatic rifles, the only thing used was the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). I have nothing that approaches the look of this weapon. FYI: Neither side had or ever used Tommy Guns.

For the shotguns, both sides used the Remington Model 11, which was an auto-loading shotgun where the barrel, not the forestock, moves back and forth between shots. The police used full-stock shotguns with long barrels, while the Barrows used sawn-off versions (as shown). I have nothing that approaches the look of this weapon. Neither side used double-barrel, break-open, or pump-action shotguns. (The Texas Ranger Museum falsely displays a pump-action shotgun as one of the Barrow weapons. It is not.)

For the handguns, these were the typical revolvers and semi-automatics of the period.

Book of Days

A very specific description of one of the two shotguns is in the lines. Ruth let’s us know that it’s a “custom made J. Purdey and Sons, British, side-by-side, engraved full sidelock”. What does all that mean?

J. Purdey and Sons was a British firm that made shotguns and rifles, and specifically double barreled side-by-side shotguns from about 1890 to 1940. There is nothing particularly distinctive about the shape of a Purdey shotgun, so even a gun collector wouldn’t necessarily spot one immediately. The gun would have internal hammers, rather than exposed, but so do shotguns of several companies. Ruth probably noticed the manufacturer’s mark on the gun frame. Custom made shotguns might have a buttstock specially cut to fit the owner’s arm length and upper body contours, but this could also have been an after-market adjustment. Engraving on a rifle or shotgun is a very expensive addition. And it is true that Purdey shotguns have an especially high value amoung collectors, so her estimate of thirty to fifty thousand dollars is spot on, assuming that the gun is in nearly mint condition.

So here’s a case where the playwright has done all of his homework and gotten all the details right. Unfortunately, he picked quite an expensive piece to try to replicate for stage. Good luck trying to find a double barrel recessed-hammer shotgun without a trace of rust and with engraving covering the center “box” section (the sideplates). Better perhaps to just find whatever two double barreled shotguns you can and simply polish the heck out of at least one of them.

Brigadoon

With the exception of anglicized nobles in the 17th and 18th centuries, Scots never wore the sword off of the battlefield, but that won’t stop directors from wanting many in the cast to wear them. And of course you’ll need some swords for the sword dance. But which sword? The unmanageable two handed Claymore or the basket hilt single hand sword of the 17th century? As the time period for this show is fantasy, the weaponry choices for the Highland dance can be anything you want. The costuming suggests using traditional Scottish swords, but I’ve noticed that even modern Highland dancers from Scotland don’t use Scottish swords when they perform or compete. Scottish two-handed broadswords (Claymores) with their very long and broad blades are simply too large to carry or dance over. Single-handed basket hilts swords are more manageable, but the three-dimensional hilts lift one side of the blades up from the floor by a couple of inches. Dancers can easily catch their toes on the raised blades and kick the weapons flying out into the audience. For that reason modern Highlanders tend to use very flat hilted society swords that can lay flat against the floor. I strongly suggest that this is the way to go on this show. Let the non-dancers wear the basket hilts.

By the way, the dance is traditionally performed with two crossed swords, but there is no reason why it can’t be done with a crossed sword and scabbard.

The show also needs a knife to be drawn and pointed, and you have a choice in terms of traditional Scottish daggers, but don’t compromise on this. A long bladed dirk with no hand protection was worn at the waist – not the leg. The Scots did have a small knife tucked into the fold of their high wool socks, but this is not a dirk but rather the three inch bladed Skean Dubh. This little thing is just too small to be a credible threat, assuming that the audience can even see it. Don’t try putting the larger dirk on the ankle or in a boot – it just doesn’t work for the style nor the period nor for the comfort of the actor.

Bullshot Crummond

Just a word here about the sword fight near the end of the play. Naturally, this is a live-action cartoon, so whatever the fight looks like is fine so long as it’s funny. That is the first and last consideration for this play. But if you really feel compelled to add some “historical accuracy” or character delineation to it, read on.

Otto lets it be known that he studied at Heidelberg (we would have expected nothing less) so that means that he is well versed in that college’s distinctive style of sabre fencing – very different than the style Bullshot would have studied at Cambridge. Crummond would fight in Olympic sabre fencing (very quick snap cuts to the head and thrusts to the body with a very light, flexible and blunt sword while protected with a mask). Von Brunno would be skilled in the Mansuer style (cuts only to the face using a heavier, stiff, and razor-edged sword – and no mask!). Of course, the swords are Otto’s, so they are the heavier style (the schlaeger blade). But, again, why put realism in this show anyway?

At one point in the fight Bullshot describes a move he has made as a “parry vitesse”, which by the way is not a real fencing term. Roughly translated, he seems to be saying that it was a “quick block” or “parry at speed” (as though one would ever do a slow parry?). More interestingly, he describes this parry that occurred at the end of his own attack sequence, which means that the last move was an attack by Otto, parried by Bullshot. Then Otto asks if he should do an “attack vitesse” (speed attack). Again, no real meaning here. There are ways to choreograph this so that it matches the words and also makes physical sense, but don’t rack your brains too much trying to make sense out of this. The author didn’t so why should you?

Camelot

Ah, Camelot. That lovely mythic tale about English knighthood. Written from a Victorian perspective. Translated from French-Norman-Renaissance sources. About a post-Roman pre-Saxon king.

The Arthur legend is a fairytale fantasy, so a “historically accurate” production is both laughable and doomed to failure. It has no relation to any real time period, so you can design it in that Disney/Medieval neo-thirteenth century storybook setting and feel comfortable that that is what the audience expects. The legend has always been popular, and much like the Robin Hood tale keeps gathering the attributes of the people who have taken it close to heart, so it is no coincidence that we see so much of Victorian Romanticism in the present incarnation.

The true Arthur would have been a Celtic/Briton warrior chieftain, leading a relatively small tribe by his position as the best warrior of the group, not because of his lineage. His fellow warriors would have numbered between a dozen to usually no more than a hundred men. They had horses but no stirrups, and no broadsword and certainly no code of chivalry. But, like so many myths, the name of a strong warrior survived hundreds of years, through the Roman occupation, the Saxon invasions, the imposition of the Dane law, conversion to Christianity, and the Norman Conquest. When the Normans developed their own culture of the sword and spur, romantic tales of early “knights” were created around extant stories of famous warrior kings. That’s why the cast of characters’ names are a mix of French, Anglo and Celtic, and elements of each passing religion get attached to the story, each group adding something to the tale.

Many moderns enjoy trying to peg the story of the round table and Camelot onto one of several “Artvr”’s that did exist, a mix of Celtic petty chieftains and later Breton/Roman warlords. But these are just flesh and blood markers on which to hang an illusion. [Even trying to find someone with the name Arthur is an error, for Arth is Celtic for bear, a warrior’s sobriquet; a nickname. It was never used as a given name until long after the Saxon domination.] So there can be no “historical accuracy” when trying to design this show. Arthur belongs to the time of Sleeping Beauty and Snow White, a fantasy of knights in armor no different from that concocted by Don Quixote’s fevered delirium.

As for Excalibur, whatever you imagine that sword to be is exactly what it should look like.

Carmen

The typical firearms for the period are all single-shot muskets and pistols, and it is right during the time when European armies are switching from flintlock to percussion lock, so you can get away with either style. The sidearm is a standard military sabre, but no pistols yet. Pistols were used by irregular units, and were not part of regulation armament.

For the knife fight, the typical Gypsy weapon would be the Navaja, a single-edged slightly curved folding knife which makes a ratcheting sound on opening. Unfortunately, Navajas are no longer imported into the United States, and no one manufactures them here, so a reasonable alternative is any large folding knife or a medium sized fixed-bladed knife.

I get a lot of questions concerning which weapons that should be displayed during the March of the Toreadors. While there is no set rule considering what should be presented, there are a couple of things to keep in mind. The sword of the toreador has a slight but sudden bend about five inches from the tip. Not a curve: a bend. This bend allows the toreador to better strike into the bull from above, rather than having the blade skip off its back. But that also means that the sword, called an “estoc” does not have a scabbard. Ever. It simply can’t fit into one. For the same reason, the estoc is never worn. Ever. It is simply presented to the matador when he is ready for the kill.

Most people believe that the sword is held under the cape for all of those stylish moves of the cape. Not so. What the matador uses to hold the cape out is a two or three foot wooden stick called the muleta. He trades it out for the sword before the moment of the kill.

Carnival

There is a sword box illusion required for this show. Most theatres won’t have access to a large magic house in order to rent one, so will have to build their own. There is nothing complicated about this illusion, but there are two ways of doing it.

Version A: The easiest is actually the flashiest. An assistant steps in the box, immediately the swords are thrust in, and then the top and sides of the box are all folded down, showing all of the swords and … the assistant has disappeared! Usually through an escape in the back of the box and then through a curtain, but sometimes through a trap door on the bottom of the box and into an impossibly smaller box on which the sword box is resting. The assistant has to curl up into a tiny ball, convincing the audience that no human could possibly fit inside that minuscule space.

Version B: Much riskier, but a wonderful illusion when the audience is right on top of or surrounding the action. This time the box is on top of a completely open frame, absolutely no chance of an escape. The assistant steps into the box, the magician says something to her/him, and she/he answers loudly. The swords are thrust into the box, with the assistant still talking from inside the box! The box is spun around, the swords removed, and the assistant steps out, none the worse for wear, and the sides drop down showing that there was no escape possible. This illusion requires very careful planning and quite a bit of glow tape inside the box, for the assistant has to contort into a very specific shape so that the swords will slide through the empty spaces. Each sword goes in in a prescribed order, so that the assistant can press her body against each sword blade in turn to create the next clear space. The glow tape is merely to mark where the first couple of swords are going to go.

Cherry Orchard

Two guns are shown in Act II, a rifle with a sling for Charlotta and a revolver for Epikhodov. Since the play was written in 1902, and the revolver obviously has to fit easily in a pocket, something like a British Bulldog or really any snub-nose revolver will do. The rifle is a slightly harder choice. Bolt-action rifles were available, but were primarily military weapons. Would this family have one? The common sporting rifles of the time would have been lever-action or simple repeaters.

Clue: the Musical

The show follows the tradition of using the six weapons of the British boardgame, designed in 1948: candlestick, knife, lead pipe, revolver, rope, and wrench. The problem comes when trying to match the knife and revolver.

The gun is a “pepperbox” style percussion pistol of 1837, not technically a revolver, but rather a multibarrel pistol. Why the gamemakers decided to use a firearm already over a hundred years old when the board game was invented is beyond me. Even stranger is the choice of knife – a bronze aged dagger (not a knife at all, really) of the style found in ancient Mesopotamia. These two items are not impossible to find, just difficult, as they are not standard items in most props cabinets.

Columbinus

The four guns used in the high school tragedy are very specific, but remember that you only need to match the profile of the guns. Don’t stress too much about getting the exact brand and model number unless you really want to spend thousands of dollars on the rental.

a) Savage-Springfield 67H pump-action 12 gauge sawed off shotgun. The key here is “sawed off” and “pump action”. Nothing else is important.

b) Hi-Point 995 Carbine 9 mm semi-automatic rifle with thirteen 10-round magazines. This one is going to be tougher to find. It’s really a pistol retrofitted with a rifle butt stock, elongated barrel and foregrip to match. 10-round clip’s are fairly short; only about four inches long, so showing one on the gun is not that crucial to the look.

c) 9 mm Semi-automatic handgun with one 52-, one 32-, and one 28-round magazine. Two “long” clips (“magazines”), that’s easy. As for the pistol, the main distinguishing feature is that the clip is in front of the trigger. The gun was not specifically identified as being the Intratec TEC-DC9 (Tech-9), but the profile is very similar to it.

d) 12 gauge Stevens 311D double barreled sawed-off shotgun. This one is a bit odd in that it is a really old-fashioned weapon, basically Grandpa’s old barn shotgun cut-off at the barrel and buttstock. Odd because it is a slow weapon, requiring the shooter to re-load after every two shots. Be that as it may, news reports at the time described the gun as having a 23 inch barrel length, which in no way looks like the photographs of the weapon. Perhaps they meant to say 23 inch overall length, but even then that is too long for what is pictured in the police documents.

Corpse!

The gun is a revolver, and for this show must be the most reliable you can find, even at the expense of good appearance, for the order of the shots is crucial to the plot. In case of an early misfire, the actor can’t simply try to fire again. One other problem is that the gun must be loaded in plain view of the audience. Unfortunately, that can limit your choices to only large caliber guns using hefty and costly blanks. The more affordable .22 caliber shells are hard for the actor to manage and the audience to see.

One option, and the stage directions in the script suggest this, is to use a dummy gun to load in front of the audience, and then a twin firing version that is switched out for the appropriate shots. Switching out is difficult, but not impossible. The tough part will be in finding the identical guns. This has become more of a problem in recent years, one that the original production didn’t have to worry about. When the script was written it was fairly common practice to use modified real guns with full chambers.

For the sword fight, the weapon is described as a sabre. But it is not the military sabre, rather the light Olympic style fencing sabre that is required here. A particularly gruesome effect is called for at the very end of the play, as Powell is exposed, not only impaled on a sword, but also stuck into the cabinet wall. If the Major is already wearing a light harness under his shirt, a dummy sword hilt can be screwed onto the front, and a short length of thick high tension wire (already connected to the wall) can be clipped onto his back. When the cabinet is opened, the Major can lean forward, making the wire taut, and for all the world it looks like the blade has gone through him and he’s now stuck to the wall. He can even gently swing slightly side to side. Creepy.

But it is the killing of Powell before he is shut up in the cabinet that has actually caused more headaches for several productions. In order to make the last impaled bit work, many choreographers think that the audience needs to see him run through dead center. In order to do that, they need a collapsible sword. They don’t really. All they need to do is position the final run-through so that the actor is in profile at that moment, or better yet in motion so that the run through and the closing of the cabinet can happen in one rushing action. The audience will put two and two together when the cabinet pops open later.

Actually, I talk about “those” choreographers, but to be honest, I was in that number for many years. I always used a collapsible whenever I choreographed this show. For each production I actually built four swords – two regular swords for the combatants, one duplicate collapsible for the final thrust home, and then a complete hilt with a stubby threaded four-inch bolt where the blade should be that could be screwed into the hidden harness. Since the regular sabres were outfitted with epee blades, a manual extendable car antenna made a great blade for the collapsible. I would work the choreography so that towards the end of the swordfight there would be a brief disarm of Evelyn, his sword going behind a sofa, where the switch to the collapsible could be conveniently made. There were a couple of drawbacks to this. The first is that the car antennae made a very weak blade, so that sword could only be used for a very few moves at the end of the fight, namely some very light deflections of thrusts by Powell. It was certainly far too weak to take even light cuts. Another problem is that the last section of these antennas is very thin and can be easily bent, and once bent, easily broken. So the end had to be carefully pushed in a few inches before the prop was pre-set behind the sofa, and Evelyn had to be very careful during his killing thrust. The last problem is that I was putting my actors in danger. If the antennae should ever have failed during that thrust, the actor playing Powell could have been seriously hurt. Even with that not happening, I still had to make sure that my Powells leaned forward at the moment of the kill, to prevent the tip from skimming off their chests and flying up toward their faces. I am no longer that cavalier with my actors’ safety.

The Country Wife

Written and set in 1675, a pistol is fired. Ostensibly this is the squire’s gun, but in this period pistols are still quite long and are really only military weapons, the flintlock pistol having just been invented that same year. The earlier pistols were mostly wheellocks, and very expensive, impractical for civilian defense and wildly inaccurate for hunting. The author was obviously keen on getting one of these contraptions in his play, but remember that the pistol was nearly unknown off of the battlefield. Some of the wealthy owned one or two as novelty pieces and for some delusional sense of home protection. [To the audience of the time, this would have had some of the shock value of seeing a modern middle-class homeowner pull out an assault rifle.] Although some civilians might have had a full-sized rifled musket for hunting, anything shorter lacked a true practical purpose unless one was firing at something only a few yards away. Even if you should be able to track down a wheellock pistol, feel free to use any flintlock pistol replica for this show, since the real item is so large that it just looks silly to modern audiences.

The Crucible

In Proctor’s house, scene 2, we see him threaten to whip his servant, but it would be a mistake to think that a conventional whip is the most appropriate item for this show. A farmer in this part of the world would have had no need for the full length whip, which is a tool for cattle drovers. Whether riding a horse or to impel a recalcitrant ox in front of a plow, a very short stock whip, only two or three feet long, with a very broad and flat slapping surface was probably what he would have used. The thin end of a bullwhip breaks the skin and can lead to infection and is very bad animal husbandry. And Proctor is a farmer, not a cattle drover. He mentions that he has just come from plowing, yet he only brings in his “gun”. The whip, whatever kind it is, has been in the house all day. Apparently it was included by the playwright purely as a theatrical device.

Later in the same scene, he uses a gun to hold off those who come to arrest him. The matchlock musket known as the Spanish musket is the strict historic choice, the later flintlock known as the Brown Bess is a close second, and perhaps even the far earlier arquebus is a possibility. I would suggest staying away from the blunderbuss at all costs. Although it has become something of a Thanksgiving Day icon to see a Pilgrim bearing one of these flared-barreled firearms, it was not used by farmers or hunters (or even by the Pilgrims), and indeed creates an automatic laugh from the audience since it makes Proctor look like Elmer Fudd. Blunderbusses were used rarely in the colonies before the late 1700’s, and none were in the Plymouth area before that time.

Why does Proctor have his gun with him when he has been plowing all day? Plowing is hard work and requires two arms to control the plow while the oxen drives forward, so where would he put the musket? Are we to think that he wore it on his back while working? Completely impractical. That he left it leaning against a tree while he plowed, ending up hundreds of yards away from it? Then it would be of no use to him in case of an animal attack. No, Proctor returns with the gun because we, the audience, need to believe that the gun might be loaded, which would not be the case if it had been in the house all day.

But in reality whatever gun Proctor has would of course not have been left loaded, for the powder left in the barrel would attract moisture and quickly corrode the steel. Even walking with a musket can cause the powder and ball to shift away from the ignition point, which is why guns for hunting were loaded only once the quarry was sighted and the hunter could stand, load, and shoot without further traveling. The Spanish matchlock takes about three to four minutes to load and prep the lit fuse before firing, and the later Brown Bess also takes about a minute to load, so anyone seeing Proctor pick up a gun and point it at them would know that it is not a credible threat. Arthur Miller took some artistic license, and who are we to argue. The gun needs to be a flintlock musket.

No one else needs a gun in this play. Some productions like to have guards standing by with muskets or truncheons in the court scene, but this is not only inaccurate (there was no standing army nor even a constabulary) but it takes away from the powerful and more frightening concept of terrible injustice occurring by the sheer force of public panic rather than force of arms. Even in scene 2, when men come to arrest Proctor, there is no need for guns, for these are his neighbors and friends. The dramatic tension is actually heightened when they are unarmed, for Proctor’s choice becomes a terrible one of becoming a murderer and outlaw or trusting that his town will finally come to his defense.

In the final scene, we see the prisoners shackled. Just a note here: shackles were difficult and time-consuming to place and remove and the better ones were built with a turn-key and threaded bolt rather than a modern switch-key lock. But key and lock shackles were uncommon, and most were built without a lock at all. They were cold riveted closed by a blacksmith, and you remained shackled until a blacksmith would cut them off. By the way, prisoners were charged for their own shackles and for the cost of food and housing while they were in jail. Even if found innocent of all charges, they still had to remain in jail until all costs were paid for by the family of the prisoner. So when Procter is led off in scene 2, he is worried not only about proving his innocence, but about the very real chance of economic ruin no matter the outcome of the trial.

Cyrano de Bergerac

The real Hercule Savenion de Cyrano de Bergerac arrived in Paris at the ripe age of sixteen, and died at the age of thirty-one. His personal weapon would have been the cut and thrust rapier and he almost certainly would have used a secondary weapon in the left hand. But the author Rostand specifically describes the attributes of a much lighter weapon – the smallsword of the early 1800’s. The duel in rhyme especially makes reference to moves only used in this later style of swordplay, and trying to make the fight conform to the historically correct sword blade is an unnecessary headache. No mention is ever made of a left handed weapon, and it just feels wrong to have him use one. The very light and quick style of swordplay of the nineteenth century, concentrating on finesse moves of the wrist, will help to show off the dazzling superiority of Cyrano’s swordsmanship far better than will a heavy cut-and-thrust fight of the 1600’s.

This play, written in the grand emotional romantic style already out of fashion at the time it premiered in 1885, was nonetheless wildly successful. Rostand wrote using the same swashbuckling clichés made popular by Dumas and Sabatini. Audiences did not demand historical accuracy, and it is usually a mistake to try to force it onto a fantasy such as this. Do what is exciting.

The duel itself is only roughly laid out, but there are some clues as to what the audience might see. Cyrano bates Valvert mercilessly until he can take no more. At “so be it”, it almost seems inescapable that he draws his sword at this time. Cyrano does not, not until he describes the moment in the ballad “then out swords, and to work withal.” Does the fight begin here? There’s no reason why it cannot, with the rest of the lines coming in and around the fight moves. Or some choreographers may choose to delay the crossing of swords until after the first “thrust home”. There is no right or wrong, merely a directorial choice. The only truly specific fencing terms used in the poem are “… beat, pass … ”. To beat means to tap the opponent’s blade to provoke a response or to push it out of the way. Pass is simply a walking (crossing) step forward or back, as opposed to an advance or retreat. Less directly, the line “… note how my point floats, light as the foam…” is suggestive of some very tight point work which eludes Valvert’s attempt to engage Cyrano’s blade with his own.

It’s easy to forget that there is only one fight shown in the play. Some directors like to put in a staged “fight against the hundred” in between Acts 1 and 2, but this is a grave mistake. Unless you actually have one hundred fighters on stage, the fight becomes ridiculous, the audience obviously seeing that you’re using the same actors over and over. More importantly, a fight that exists in the audience’s imagination will always be superior to whatever can be choreographed, so let the words of Act 2 provide the excitement of what they have not seen.

The battle scene in Act IV of course does not actually have a battle, although many directors will want to have a Spanish army overrun the stage. When that is the case, it is better to use a heavier blade on the swords that can survive the bigger bashing moves required. You’ll risk a lot of broken blades if you stick with the lighter dueling epee blades.

The soldiers of Cyrano’s unit are cadets, therefore not full soldiers. Perhaps someday they will be Musketeers, but not yet. It is likely that they have swords but that their primary battle weapon is a pike or halberd. Since for this scene they have been besieged for some time, it can easily be justified that as other soldiers have died, muskets, arquebuses, crossbows, lances, all in various states of disrepair, might have been scrounged together by individual soldiers and all have found their way onto this scene. By the way, the entire concept of a cadet is another anachronism that must be ignored. The term “cadet” has changed over time. Whereas now [and in Rostand’s time] it means a student at a military college [and those didn’t exist in Cyrano’s time], from 1650 to 1775 it meant a younger son of a noble family who entered the military to try and establish a career there. But in Cyrano’s time, cadet merely was the general term for a younger branch of a noble family or specifically the youngest son of a nobleman.

One last note: Even before the Gerard Depardieu version, many directors and choreographers have had Cyrano win the Act I duel by the end of the poem, but magnanimously not kill Valvert, only to have the horribly embarrassed Valvert try to sneakily run Cyrano through when his back is turned. Cyrano miraculously escapes and in a brilliant counter move, dispatches Valvert, but with regret and almost against his will. Very dramatic and touching, and adds a level of compassion and humanity to Cyrano. This helps directors soften Cyrano’s image as a cold-blooded killer. I have found that this is not because of any squeamishness on the director’s part, for these are usually the same people that want to put in three or four extra fights in the show. No, they make this change out of their belief that a hero would never choose to kill someone unless pushed to extremes.

This is a lovely thought, but is not supported by the script. That species of compassion is an alien concept to any but those of the mid to late twentieth century. Cyrano does not duel with the meddler because the meddler is of the common class. When the noble-born Valvert challenges him, Cyrano offers him every opportunity to back away from the fight, even while publicly insulting him. But once Valvert draws his sword, it is acknowledged that one or the other will die. Diminish that in any way, and Cyrano is not a man to be feared.

True Stage Weapon Story: Much like Hamlet, the role of Cyrano is often given to an experienced and mature actor, well versed in souring lyric poetry but sometimes a bit beyond his better years of athleticism. In a production in San Francisco, a very well regarded actor in his sixties tried to recreate the role that gave him local renown when he was in his late thirties. Alas, his earlier performance should have stayed as fond memory, rather than as a cruel point of comparison. The final “as I end the refrain…thrust home!” was usually so off the mark that most nights poor Valvert had to fling himself onto the blade if there was to be any chance of his dying. The effect was less a demonstration of Cyrano’s skill than that of a confused and weary Valvert playing the noble Roman and falling on the sword so as not to embarrass Cyrano.

Dangerous Liaisons

[see Les Liaisons Dangereuses]

Deathtrap

The following is from an e-mail that we received at Weapons of Choice from a harried props master:

“I’m not sure what you might have in the realm of guns, the prop list called for a Smith and Wesson 38 snubnose with blanks and a Smith and Wesson 38 long barrel with blanks. We also need a dueling pistol, large with a light brown finish. All of these are working models.

As far as set dressing purposes, the props list calls for a Smith and Wesson 38 long barrel, a German Luger, 5 small antique pistols and 2 muskets.

For knives, I need a black handled knife and a gold handled dagger, these are “working” props, although obviously I assume that means they fold over or something as to not hurt the actor.

We also need a curved sword and three knives with sheathes for set dressing.

We need 2 crossbows (one as cover) three garrotes, (one a “working” model), and a spring plunger crossbow bolt (whatever that is). Also a screw on crossbow bolt and 3 regular crossbow bolts (one used, two dressing.)

For set dressing, we need a sickle, cleaver, four pair of leg irons, two pair of antique cuffs and a decorated Indian stick with metal rod.”

It was my great joy to let her know that she needed very few of these things.

If you are about to do this play you’ve already been confronted with the massive props list in the back of the script (the above e-mail actually referenced only a few of them). Please don’t feel that you have to find all of those items. Remember that that is merely a list in which someone from the original production very carefully notated every item used as either a practical prop or as set dressing. It in no way should be taken as a mandatory list for your show. Most of it can be ignored – just make sure that the walls are covered with a nice assortment of fun and frightening weapon replicas. Even the practical weapons that the technicians of the original show found may not be what you need for yours. Remember: your job is not to recreate the Broadway version. Your job is to tell the story in the most efficient manner. So your list of practical props may include some very dangerous ones as it is. Stripped down to the basics, here is truly what you need:

• Two blank-firing guns, and it is helpful if they have different looks, but that could merely be a difference in barrel length. Revolvers are always preferred over semi-autos because of their greater reliability.

• Trick-release manacles or handcuffs. Only the stage directions refer to them as “Houdini-style”, so if the old style proves hard to find, you can easily switch to the more modern police style.

• A mock garrote, and a blood effects garrote. There are a few out there, which ooze out fake blood from a reservoir in the handle, but if you can’t find one, you can always have the victim palm a blood pack, reach for his own throat and apply the blood himself. Here’s how, using a real makeshift garrote – that’s right, a real wire. After the wire is wrapped safely around the victim’s neck, let the attacker simply rest his forearms against the victim’s back. The victim can then press forward into the wire as far as he feels comfortable. After two seconds, the victim would naturally grab at his own throat to try and release the wire, right? That’s when he brings up the small blood pack that he has palmed during the “struggle”. There should be plenty of places on the desk to hide it. Once the blood pack pops against the wire, the blood oozes creepily through the victim’s fingers. Very effective.

• A firing crossbow, which no matter what you do is a ridiculously dangerous weapon. A standard crossbow has a draw strength of about 250 pounds, and even though some theatrical varieties have only a 50 lb. draw strength, the force of the low velocity projectile causes severe damage when it hits soft tissue. Assume that the crossbow can and will fire without warning and so must always and forever be pointed in a safe direction. There are some trick crossbows that don’t fire the bolt [arrow] but instead when the trigger is pulled the bolt drops into a hidden compartment in the stock. If you can find one, use it for your show.

• A thin bladed knife, a stiletto. Used to jimmy the lock in the desk. This is a pantomime movement, so the knife need not be especially sturdy.

• A log from the fireplace for hitting over the head. Make it out of foam rubber, not Styrofoam, with a thin wooden core if the director insists on actually hitting the actor on the head, although I hate the idea and think that a clubbing technique as described in the earlier chapter is a better way to go. “I’ve got news for you; Styrofoam hurts.” No kidding; a clubbing to the head can even cause a concussion and minor cerebral bleeding..

• Likewise, I don’t like using a retractable bolt (arrow) for the stabbing. No retractable item is ever safe, nor is stabbing anything into a “protective” guard placed underneath the costume on the actor’s chest. People have died this way, and for what? For a show?!?. Here’s one way around that. On the plus side, crossbow bolts are fairly short, so hiding the stab is a lot easier than it would be with, say, a medieval dagger. You can always use a blunted regular bolt, and use the attacker’s arm as the “collapsible”. It’s a magician’s trick, hiding the sliding bolt from the audience’s view. Here’s how: holding the bolt with the downstage hand so that at least half of it is showing, the stab is done straight in, allowing the bolt to actually strike the victim. The attacker’s hand is kept very loose, which allows the bolt to slide up the forearm, hidden from audience view. The attacker’s hand can slide all the way up to the victim’s chest. With a little practice, you can even do a quick “relax and grab” during the pull out. The bolt floats in air for a second as the hand withdraws slightly, and grabs the bolt at the original position. It can look great even in close up, so long as the forearm covers the bolt at the moment of the stab.

• A bolt (crossbow arrow) that somehow can be stuck into Clifford. The simplest is to have him wear a strap underneath his shirt that has a threaded nut built into it, and a bolt with a matching threaded end. He can simply screw in the bolt before coming back on stage. Make sure that this fake bolt is a bit shorter than the real bolt fired from the crossbow.

Desert Song

French Foreign Legion (actually Spanish, but we shouldn’t quibble), therefore the soldier’s weapon is the bolt-action rifle.

Diary of Ann Frank

At the final scene, “Nazi’s” come to arrest the Van Dams and the Franks, and history gives us some specifics here. One uniformed German SS sergeant and three (sometimes four) Dutch security police in plainclothes would have been a standard detail dispatched for the action. The weapons they carry should match the way they are costumed. There would be no German soldiers in the group, so no rifles. A traditional German officer would have a pistol – a Luger or Walther semi-automatic. While it’s possible that uniformed or non-uniformed Dutch collaborators might have the same, it is far more likely that they would have generic revolvers with 4” barrels. The security forces of German allies were usually given older guns, the newer and more highly-powered weapons going to German frontline troops.

Escanaba in Da Moonlight

This play and the prequel, Escanaba in Love, deal with deer hunters of the Upper Peninsula area of Michigan. Their weapons could be bolt-action rifles, pump shotguns, semi-automatic rifles, or large-caliber lever-action rifles (listed in decreasing order of popularity).

The script specifically makes mention of a “Remington 250”, which is a .22 caliber cartridge, not the rifle. Normally, this would be used in a Remington 700 rifle, which is what we see in the movie. Although it has some acceptance amoung hunters, the use of a rifle of such small caliber but high velocity has a serious drawback for large game. In the hands of a hunter of average skill, it is likely to cause a painful wound rather than a quick kill. It is a squirrel rifle, not a deer gun. But we are stuck with it since the script is so specific.

The script also mentions a “30-30”, again a cartridge size not a rifle description. The most likely rifle to use such a bullet cartridge is a lever-action. In the movie, Jeff Daniels has a Winchester lever-action.

I made a grievous error in the first edition and wrote that shotguns would not be used. I was completely wrong. Although rifles are far more accurate and allow for kills of between 300 to 600 yards away, many hunters fire only within 100 yards, so a single large slug from a shotgun can accurately and effectively bring down the quarry at such short distances.

Eugene Onegin

The opera was written in 1879 by Tchaikovsky, but from a Pushkin lyric poem of 1833. Costume settings for the opera therefore tend to be set in either of these two times, and that will affect the choice of the pistols for the duel. Those that are set in 1833 need to use single-shot pistols, but those set in 1879 can get away with revolvers.

Evita

Rifles and pistols pop up in several scenes. Although Argentina produced most of its own armaments, the styles follow the same pattern as weapons found throughout Europe and the US, although usually a generation behind. Rifles for this period would be bolt-actions very similar to the bolt-action German Mauser, while pistols cover all of the styles found during the mid-20th century.

* Random art note: Every single production that I have seen, including the original, gets the dancers’ and tango singer’s costumes wrong, putting them in a sort of ruffled sleeved conga/rumba/flamenco outfit and dancing some Cuban/Brazilian thing. It also doesn’t help that the song he sings is not a tango. These are not trivial issues for this show, as it shows Andrew Lloyd Webber’s lack of understanding of what the Argentinians felt was their isolation in the twentieth century, a feeling that allowed a charismatic figure like Peron to sweep into power.

Argentina created the tango, but only for the citizens of the capitol city, Buenos Aires. It was they who danced the tango, who sang the tango, who lived the tango. Almost always in a minor key, with a driving 4/4 beat that pulls the dancers along in an eight step march to a relentless and bitter destiny. The dance itself is not rigid: both the dancers and musicians are free to improvise in a fruitless effort at breaking away from the coming downbeat. The dancers especially try to create a sanctuary within their dance, the man choreographing, the woman improvising, ever searching for a place of safety, of escape, of something in the midst of their passionate embrace that can save them from the darkness in which they live. The closeness of their bodies becomes a desperate attempt to create a single entity, a vain attempt to create something stronger than either one alone, something that can overpower life, overpower the night, overpower death. But even as they try to sustain the intimacy of a pause, to brighten the moment with a flourish, the music plunges them back into the painful reality of a world cruel and uncaring. It is the music of people trapped in the poverty of a large city, and even the happy tangos carry an undercurrent of loss and melancholy, of disenfranchisement. Here is no joyous celebration of life as one finds in the music of Brazil or the Caribbean, and the male tango dancers and singers would only wear the uniform of the city, the two piece suit made for prowling the streets at night looking for solace. These are people who feel that they are lost Europeans, living thousands of miles away from civilization, surrounded by a vast continent that they would rather ignore than embrace. Buenos Aires was and still is an island unto itself.

The Fantastics

Make sure that the properties master and the director are on the same page as to what sword you want. There have been so many times at our rental company where we’ll get an order for one type of sword, only to get another call one a week later when they find out it won’t fit in the trunk. Seems silly to have to remind people of this, but there you are.

Fiddler on the Roof

The show is set in 1905, so the rifles carried by the Russians, if any, should be bolt action rifles similar in style to the Mausers of WWI. No one in this play, even the police chief, needs a sword. Although he would more than likely go through his daily routine unarmed, it is not unreasonable to costume him with a pistol.

Forza Del Destino

This opera calls for a gun to be thrown to the floor, which then fires and kills the Marquis. First problem: no gun, real nor replica, can survive being dropped to the floor. This is especially the case for the single shot pistols of the 18th century, because the hammer is very exposed and most of the frame is wood. Second problem: No gun can be made to fire reliably when dropped to the ground. Yes, it can happen, but the gun has to turn in such a way so that the hammer would hit the ground first, with the force being directed forward, not back or sideways or down, and even then it’s hardly a sure thing. Third problem: the drop has to be controlled so that the barrel is pointing directly at the Marquis when it hits the ground. If that doesn’t happen, the audience laughs because it is so obvious that he couldn’t have been shot.

What to do? First, buy a bunch of very cheap replica pistols, because most are going to break. Better yet, build them yourself completely out of steel and paint them to look like wood. If you buy very expensive sturdy guns, you’re just throwing money away, because no gun is sturdy enough to be repeated dropped. Second, use an offstage sound for the gunshot. There is no safe way to get the gun to fire on impact, and absolutely no way to create a safe discharge down the barrel of such a thing. Third, practice that drop so that the barrel always ends up pointing exactly where you want. Good luck.

God’s Country

Some very specific automatic weapons are mentioned in the props list, but not in the lines of the play, so all you need are some very scary modern assault weapons. The problem comes in the scene where we are supposed to see a gun rather expertly dismantled and reassembled in the process of cleaning it. There is nothing easy about this, no matter what gun or replica you get. I’ve seen actors blow this and accidentally send springs and parts flying across the stage (one time into the audience). You’ll need to rent a (costly) real rifle that has been made safe for theatre, and then get expert training for your actor. Expert.

Grapes of Wrath

In the latest stage version, Tom disarms a deputy sheriff who has accidentally shot a woman in a crowd. The gun is described in the stage directions as being a semiautomatic pistol, and that Tom removes the clip and then chambers out the remaining round. Please don’t feel that slavish adherence to the stage directions is necessary or even wise. For one thing, having a deputy carrying a semi-auto in the 1930’s is as likely as having a modern officer driving his patrol in a Masserati. On a practical level, you may have read elsewhere in this book that semi-auto’s are notoriously unreliable as well as too loud for most theatres. So go ahead and change the pistol to a revolver. Tom can still open the gun and empty it of its “bullets”, so the intention of the moment need not be lost. And don’t let the gun drop to the ground. It will break.

Guys and Dolls

In the bar fight in Havana, a bottle breaking over the head is included in the stage directions. If you decide to include it in your fight, you might want to consider not using a breakaway bottle. Instead, try having a pre-broken bottle hidden among the other bottles on the shelf. By grabbing that one and quickly going into the swing, the audience will never be able to see what the actor has in his hand until just after the bottle smashing bit. The sound of the glass breaking can come from a crash box off stage or behind the bar. You’ll save a bit of money and keep the stage safer for both actors and audience.

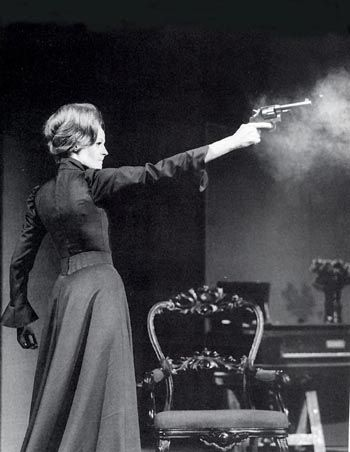

Hedda Gabler

This play, especially when performed in the US, often gets the pistols wrong. The biggest reason for that is our immediate assumption that a pair of pistols must mean dueling pistols. So let’s clear up some terms.

Dueling with pistols began in 1711, blossomed after 1780, and then slowly dissipated into oblivion by 1880. With the exception of the American West and South, dueling was strictly performed with single-shot muzzle-loading pistols. Even after reliable multi-shot revolvers were invented after the mid 1840’s, duels of “honor” continued to be conducted with single-shot pistols, so that the entire affair would not turn into a bloodbath. One shot each, thank you very much, and if both participants miss, everyone goes home healthy.

Pairs of single-shot pistols, in a custom case, were often prized purchases, even if one had no intention of ever actually dueling. Civilian men of means would buy them to increase their sense of manliness, and gun sellers found that they could easily persuade a potential gun buyer to purchase two rather than one handgun. The wealthier the client, the easier the sale.

Military pistols are another matter altogether. Often presented as gifts to higher ranking officers, they were generally the best examples of whatever was the common practical firearm of the time. In the single-shot era (approx. 1700 to 1850), it was sometimes a brace (pair) of pistols, but more commonly just one very nicely engraved piece.

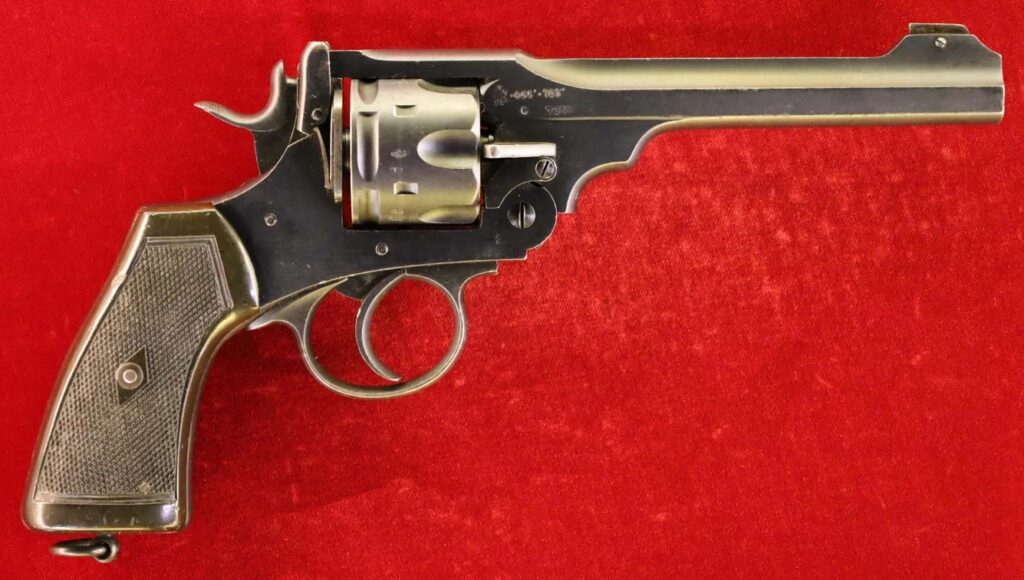

The play is set in 1890. We can consider her age to be around 20, (any older and at the turn of the century we are talking serious spinster). For him to have purchased a matched set of single shot dueling pistols during the 1840’s, even if we was only 20 himself at the time, he would have to be 70 now, and have fathered Hedda when he was about 50. Of course possible, but we’re kind of pushing it. Shave twenty years from his age, and the guns would have been purchased between 1860 and 1880. So no matter what, these are revolvers, not single-shot pistols.

Certainly by the time Hedda’s father became an officer (let alone a general) single-shot pistols were long forgotten relics, militarily speaking. So what he had were revolvers. And we know something else: they were purchased after 1878.

[HEDDA, dressed to receive callers, is alone in the room. She stands by the open glass door, loading a revolver. The fellow to it lies in an open pistol-case on the writing-table.]

So … the playwright calls them revolvers.

[She goes to the writing-table and opens the drawer and the pistol-case; then returns to LOVBORG with one of the pistols.]

So … they can’t be percussion (blackpowder) revolvers, because you can’t simply leave blackpowder weapons loaded in a drawer. Blackpowder draws in ambient moisture – the powder would lose its potency, the inside of the chambers would rust in a matter of hours, and the gun would be ruined from corrosion in a matter of a few days. And she doesn’t give him percussion caps, blackpowder and wadding needed for a percussion revolver. No, these guns are loaded. And if stored loaded, they are modern-style cartridge revolvers.

Brock – “She will have to explain how the thing happened—whether it was an accidental shot or murder. Did the pistol go off as he was trying to take it out of his pocket, to threaten her with?“

Single action revolvers of the early 1870’s can’t accidentally fire by pulling the trigger. The trigger doesn’t work unless and until the hammer is pulled back first. Two separate actions: so no accidental firing when pulling it out of a pocket. Brock would not even mention that scenario unless he knew that the gun was double-action.

Everything here makes it clear that the only possible weapons for this show are a pair of double-action revolvers, commonly found throughout Europe by 1878. Were they military pistols? Possible, but not terribly likely. Military firearms tended to be large caliber: great stopping power with a single shot, but man, what a kick from the recoil! Also, the huge amount of sound doesn’t make for a pleasant experience in the days when recreational shooting was done without earmuffs. And larger caliber ammunition is more expensive than smaller caliber, If Hedda and her father could pass the time away firing off several dozen rounds at a time, it was most likely with a pair of .22 or .32 caliber revolvers.

I Hate Hamlet

The fight between Barrymore and Andrew can and should be as elaborate as you can imagine, and this is a great chance to throw in every movie swordfight cliché ever seen. Barrymore is, after all, not only provoking Andrew into fighting but also teaching him how to be a swashbuckler. Jumping over the sword, slicing the candle on the mantle, going body-to-body for the dramatic lines, as well as every cheap sight gag in the book should be in this fight.

The swords are Barrymore’s of course, and as such are either his own practice fencing weapons or theatre/movie props from one of his shows or films. No matter which, the blades should be light fencing weight, such as the epee, for movie swordplay in Barrymore’s time was based on Olympic fencing (even the “broadsword” fights were elaborate versions of sport fencing).

Huck Finn

see Tom Sawyer

Into the Woods

The two princes are usually costumed wearing swords, and there are two ways to go with these, depending on how they are going to be costumed. Believe it or not, there are two fairy tale traditions from which to choose, and the best way to visualize these is to look to the Disney animated classics for examples. If the look is “medieval fairy tale” such as Sleeping Beauty, then a very light version of a straight edged broadsword would be the right sword to use. If the look is more “folk fairy tale” like Cinderella, then one should go with gently curved sabres.

Jekyll and Hyde

The novella was written in 1886. There is a gun in the play, and in the novel it is merely described as an “old” gun. So, how many years before 1886 is “old”? Well, the first practical cartridge revolvers are developed in the mid-1870’s, only ten years before this story. Therefore it is not unreasonable to infer that he is referring to a blackpowder percussion revolver, a ball and cap six-shooter.

A sword cane is called for, and this poses a problem for the many states in which such weapons are illegal. In those cases, I’m afraid the only remedy is to try to build one yourself.

For the throat slitting, I always advise against using a blood effects knife. Better to go with a preset blood pot and have the actor apply the blood exactly when needed (see the stage combat section, page 390, for a couple of ideas).

Kentucky Cycle

What a prop and costume budgeting nightmare! To do the show right will take several thousand dollars to provide all of the period specific items called for. On the other hand, there is some doubling that you can do without breaking historical accuracy.

From 1775 to 1860, the United States Department of War didn’t spend much on new weaponry. The same flintlock rifles that worked fine for the revolution were used for the War of 1812. Even during the first years of the Civil War, large quantities of these same flintlock muskets were simply retrofitted with percussion locks and put into use until the newly built percussion rifles could be shipped out to the troops. Be that as it may, you should probably use percussion lock muskets by the time you get to God’s Great Supper (play 5).

So it is in the first half of the play that you can save the most money. In the second half, gun evolution progresses too quickly to allow for any doubling.

The King and I

Directors often want “palace guards” to wear elaborate scimitars. Sorry, wrong continent, but for this fluff musical you can probably get away with it. This show, and the book from which it is derived, strays so far from historical accuracy that you should feel free to put in just about anything that enters your imagination. (Traditionally, warriors in Siam would have had short spears, not swords, and there doesn’t seem to be an indication that there was a standing unit of palace guards or royal bodyguards. Certainly by the time of this play, soldiers would have had percussion muskets. Muskets were part of the Siamese armament from the late sixteenth century.)

Laura

The show requires a walking cane, which is also a firearm. (“He gives his stick a sudden twist, removes the bottom part. The rest is a gun. ‘You see, it has a short barrel. It has, in effect, the same spread as a sawed-off shotgun.’ ”) For something to have a “spread” it means that it is firing multiple pellets from a single cartridge, not a single bullet. So the gun/cane is loaded with a shotgun shell, although the barrel width could be that of any regular pistol. Shotshells made so that they can fit into regular short barrel guns are common, and actually come in many calibers. The cane itself would look like an ordinary cane, except for a recessed trigger that would only pop out when the gun is disengaged from the rest of the cane. All of this means that you can use any walking cane that can come apart easily enough and then look as though it has a hollow barrel. It helps if it has a shaped handle rather than being a simple walking stick.

Les Liaisons Dangereuses

Taking place in the mid 1780’s, the fighting style of the duel in the penultimate scene should be in the smallsword style – truly the pinnacle of single weapon dueling complexity.